Here are some pictures from our May 2010 trip to Orkney.

While most of our time was in Orkney, we spent a day or so at each end in Edinburgh, where the castle overlooks Princes Street gardens.

We walked past "12 Coates Crescent" at one point, where the Scottish dance society has its headquarters.

We also saw a Parthenon-inspired Napoleonic war memorial that never got finished, but that clearly contributed to the Edinburgh's nickname as the "Athens of the North". Both it and the castle are built on hills that are the remains of the cores of old volcanoes.

The Orkney islands lie just to the north of what outsiders would call "mainland" Scotland, which you can easily see across the dividing Pentland Firth on a clear day. (The Shetland islands lie further north and east of Orkney, too far away to see.) The term "mainland" when used on Orkney always refers to the largest of the Orkney islands, which is divided into West and East segments by a narrow neck where the capital city, Kirkwall, sits.

We had an apartment for a week in the village of Stromness on the SW coast of West Mainland, a harbor town where the ferries from Scrabster in Scotland dock.

Our apartment fronted on a little square, across from the Stromness Museum.

Stromness is an intriguing town. Docks and associated buildings were built right along the water before anybody thought about streets, so the main street of the town now winds through the backyards of that front row of buildings. In some places, they had to knock down a couple buildings to get even one car's width through.

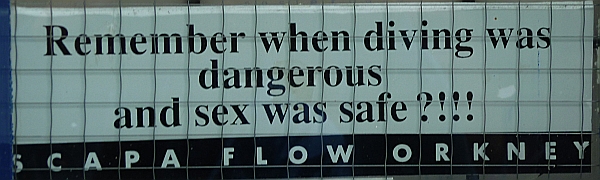

The windows facing main street were often guarded by cats, and a dive shop had this amusing sticker on the door.

One day early in the week, we took a long hike near the northwestern tip of the mainland, which has dramatic cliffs and sea birds.

The black-backed birds are guillemots, facing the cliff side with their backs to the on-shore wind. They don't build nests, but they do lay very oval eggs that roll in tight circles that are a bit less likely to take them over the edge.

The grey-backed seagull-like bird on the left is a fulmar. They love to hover, wings spread but motionless, riding the updrafts right near the cliff edge. Fulmars are "tube nose" birds whose nostrils run out along the top of their bills, as you can see in the closeup.

We also saw a few puffins (but only in the air, flying back and forth to a nest hidden by the cliffs), with razorbills, terns, gannets, and eider ducks by the water, and curlews, oyster catchers, and lapwings in the fields.

Like all of Orkney, the cliffs are sandstone, which is also what all of the prehistoric buildings were made from. Looking down, you can see that it would be pretty easy to quarry thin stone stabs with straight sides.

There's a small island off the coast there with a lighthouse on the left and some ruins on the right, close to a causeway that's passable from the mainland except at high water.

The ruins include some 10th-12th century houses and a 12th century monastery church and cloister.

On the mainland end of the causeway is the town of Birsay, which was an early power center. These are ruins of the bishop's palace from before the power shifted to Kirkwall. In one place, an arch survives although all the wall above it is gone.

A little further along the coast was a place called a "noust", where fishing boats were hauled up out of the reach of the waves. Later, a fisherman's hut was built over one of the noust "slips".

On most days, we took a number of shorter walks to see ruins of various sorts, and this early in the season, we usually had the trails and cairns all to ourselves. Most of our hiking was through sheep pastures, with stone walls and stiles. Orkney stone walls are built of horizontal sandstone chunks, with a cap row of vertical pieces to anchor the top.

On one day, we took a small "back on and drive off" car ferry over to the island of Rousay, just to the north of the mainland, where there are also a lot of prehistoric sites. Most of the islands have names ending with "-ay", the Norse word for "island".

Now, here are some pictures of the ruins themselves. The remains from the early Neolithic are mostly chambered burial cairns, either "long barrows" or "round barrows", which typically served a local community over a long period. The long barrows are narrow structures, partially divided into bays by thin sandstone slab dividers. They reminded us a lot of the "hunebed" monuments that we saw last year in the Netherlands. They say that the design may be taken from earlier wooden burial buildings, which were used for a while and then covered by a mound and abandoned. The stone versions, however, were covered by mounds from the start, with low entrance passage ways. (Where the orignal roofs have collapsed, they sometimes build modern roofs with skylights, which mean that algae can grow.)

This long barrow, on Rousay, is one of the largest ever found, 23 meters long, with 12 bays.

With round cairns, the entrance passageway leads to a central chamber that has side chambers off it.

The most impressive round cairn in Orkney is Maes Howe, which is very similar to the large cairn that we saw on an earlier trip at Newgrange in Ireland. (This only shows the exterior, but pictures of the interior can easily be found on the web.) Newgrange has a separate "window" above the entrance passage that brings the midwinter sunrise into the chamber; Maes Howe is similarly aligned on the midwinter sunset, which shines down the passage through a slot over the pivoting stone slab door in the central chamber.

Maes Howe is also famous for graffiti carved into the stones in various places by Vikings who broke in through the roof in the 12th century, more than 3,500 years after the mound was abandoned. The graffiti is written in runes, the alphabet developed by Germanic tribes in the 2nd century CE, and sounds very much like modern graffiti: "Otarr carved these runes", "Treasure was carried away three nights before they broke this mound", and "Many a woman has gone stooping in here".

There are also some cairns like this one that mix the two styles, a long barrow design that also has side chambers. It contained eagle bones as well as human ones, and there was another cairn that contained dog bones, perhaps the totem animals of those communities.

In the later Neolithic, henges and stone circles were built. There are two impressive stone circles on Orkney, right close to each other: Stenness and Brogar. The Stenness stones are tall, though only four are left of a likely original twelve.

The Ring of Brogar is one of the largest stone circles found, 100 meters across.

This picture shows the whole ring from a distance, behind a separate solitary stone.

We don't know what the circles were used for. Technically speaking, the henge is the circular ditch and mound barrier, sometimes found by itself, and sometimes with circles of wooden posts or of stones or both. Here's a picture of the henge surrounding Brogar. Note that for a henge, the ditch is inside the mound, When surrounding a fort, on the other hand, the ditch is built outside the mound. One intriguing suggestion is that the henge was intended to protect the rest of the world from whatever power occupied the circle.

There are also a number of places on Orkney where Neolithic settlements are preserved. This settlement is next to the Stenness stones, and might be the village that used that circle.

The most famous houses are those of Scara Brae, a cluster of stone buildings that got buried by sand dunes. The furniture in the houses is also made of stone, probably because wood was already getting scarce, while sandstone slabs were easy to quarry.

Many of the houses from the Neolithic right down through the Iron Age contain tanks in the floor. One theory is that limpets were soaked there in fresh water to soften them up for use as bait.

Evidence of settlement continues through the Bronze and Iron ages. Bronze age "burnt mounds" were common, large piles of mixed ash and shattered stones, apparently ash heaps from workshops where water was heated by dumping in fire-heated stones. At this site, part of the workshop building can still be seen next to the mound. Maybe it was used to boil meat for the whole community, or perhaps it was a brewery.

In the Iron Age, we see substantial defensive forts, including the "Brochs", circular forts with double walls that include a built-in circular stair between the two walls. One broch on the north mainland and one on the south side of Rousay were right across from each other. This is the mainland one.

With its impressive entryway.

And this is the Rousay one.

Both these brochs were flawed in design or construction, requiring buttressing as the walls sagged.

In both cases, too, houses were later built right around the broch, mostly filling in the defensive ditch.

These seals enjoy basking on the rocks near the Rousay broch.

In the early medieval period, Vikings overran Orkney. The earliest written history of Orkney was found in Iceland, where the Viking sagas were written down and preserved, one of which is all about Orkney. The saga tells of a dastardly murder in a hall right next to this round church. (The round church was probably built by a returning crusader in imitation of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.)

From the Viking period on, you see cathedrals, castles, and palaces. This cathedral in Kirkwall goes back to the 12th century.

The doorway of the cathedral shows that sandstone weathers pretty badly in 1000 years.

Much later, in the Resaissance, this very showy palace was built next to the cathedral.

We also saw some preserved examples of farming settlements from the last couple hundred years. The traditional design was a single building with a peat fire in the middle. The picture is smokey because there is no chimney.

On one side of the fire was the "in-by", where the people lived. The rush-backed chairs are typical of Orkney, where wood was scarce.

And on the other side was the "oot-by", where the animals lived. The smoke from the fire went out (eventually) through a hole in the oot-by roof. Note the stack of peats for the fire, and the perching rod over the door for the hens.

Nests for the geese were built into the wall.

In the original houses, the beds were in stone-sided nooks in the walls.

Later, box beds were used.

Hand-crank querns very much like this have been used since Neolithic times. (The rooster did not seem impressed.)

This detail of the roof shows how they were made, with two layers of large sandstone sheets, the second covering the cracks in the first. The whole would then have been covered with sod. (This one has had the cracks filled with mortar, as part of installing skylights for the tourists.)

A "click mill" was an early kind of water wheel for grinding grain. The grindstones were mounted on the same shaft as a horizontal water wheel, so you didn't need any gearing. The name "click mill" came from a peg attached to the mill wheel which clicked against the grain feed tube with each revolution, to joggle out a bit more grain each time.

Pigeons were kept for food, as this rich landowner's "Doocot" (dovecote) shows.

The building was open on top, and the inside of the wall was peppered with recesses where the doves could nest. Pigeon-keeping declined once turnips were introduced, which meant that the cattle could be kept alive through the winter.

From even more recent times, the World Wars have left their marks. The mainland together with a number of the southern islands form Scapa Flow, a very large protected anchorage which housed the British fleet during both World Wars. The subsidiary breaks between islands were blocked by sinking old hulks, some of which can still be seen.

At the end of World War I, the surrendered German fleet was housed in Scapa Flow until their commander one day coordinated a suprise scuttling of the whole fleet, to prevent the ships from being used by the allies.

During WW II, a large group of Italian prisoners of war were housed on Orkney, and worked on building causeways between the islands. This was presented as economic development work to link the islands, since the Geneva convention prohibits use of prisoners of war on war projects. However, the causeways, now called "Churchill barriers", did also block German subs much more thoroughly than the blockships had.

The homesick Italian prisoners were allowed to use one end of an old Quonset hut as a chapel. One of the prisoners was a gifted artist, and others were metalworkers and other craftworkers, and they ended up making over the whole hut. (The two hanging lamps in the sanctuary were fashioned from old bully beef ration tins.)

Here's a detail from the side wall. That's a completely flat panel, with trompe l'oeil painting suggesting the texture.

The Orkney Folk Festival started while we were there. We got to a concert that included Jennifer (fiddle) and Hazel (guitar) Wrigley, a pair of Orkney identical twins who have a number of CDs out. They also run the "Reel" cafe and music school in Kirkwall.

The Shetland Heritage Fiddlers performed in a pub in Stromness.

Which brings us full circle, from stone circles to musical ones..

Back to ramshaw.info home page

Updated 2010-06-07