Here are some pictures from our May 2013 trip to Wales.

We spent most of our time in north Wales in the area now known as "Snowdonia" (after Mt. Snowdon [Welsh name: Yr Wyddfa], the highest mountain in the British Isles outside of Scotland). This area was known in ancient times as "Gwynedd", which readers of the Lloyd Alexander children's books will recognize. We rented a row-house cottage in the village of Penrhyndeudreath (which translates as "headland with two beaches", usually abbreviated "Penrhyn").

The cottage had one room on each floor (bedroom/bath 2, living room 1, kitchen ground), with a nice view over the valley from the patio out back.

It made a great base for day hikes, and a fine place to play duets on our travel fiddles, each of which can pack into a 2-foot section of 2-inch PVC pipe.

We always enjoy looking for Neolithic remains, of which there are lots in Wales. On one very fine morning, we walked along a hillside track up in the remote sheep country through what was clearly a very important ritual area in the ancient days, with a stone circle, a passage tomb, a dolmen, and a nearby pair of standing stones (the one behind and to the right now incorporated into a much more recent stone wall), all within a short distance of each other.

The whole time that we were there exploring the area, we saw only one elderly shepherd with his dog, and one through-hiker. On the other hand, to get there we drove down the narrowest, winding stretch of stone-wall-lined country lane that either of us ever wants to drive on again. We have no pictures of that, as our entire energies were focused on not scraping the walls.

One type of Neolithic monument is the dolmen (one large cover rock, held up by maybe 3-5 uprights), and the general theory seems to be that these represent the oldest strand of neolithic remains. They were originally covered by cairns, and seem to have been used to house bones after the bodies had been left to "excarnate", perhaps by a family group over many years. We saw a number of fine examples.

Here, there were two together, one of which has collapsed.

Passage tombs are a different type of monument, and it's thought that they come from a somewhat later period. (The most spectacular examples of passage tombs are Newgrange in Ireland and Maes Howe on Orkney, both of which we've seen on earlier trips.) These are larger cairns with a narrow passageway entrance and often multiple internal chambers. Perhaps these were used by larger communities and over longer periods of time? Sometimes you can still see stones marking the sides of the passage entrance, and pottery finds indicate that this forecourt area was used for repeated rituals. (In this picture, the herring-bone stone at the far right is reconstruction that continues the sweep of the original forecourt wall.) A large cairn would have covered the roof slab and a considerable area behind it.

Here is one of the internal chambers from a passage grave whose roof is gone.

Stone circles and henges (circular earthworks) are generally thought to have been from a still later period. It's not clear what they were used for, but they are not generally associated with burials. However, the overall chronology of the different periods is problematic. There is one site that we saw on Anglesey (the large island off the coast of Gwynedd) where a passage grave was built in the middle of a pre-existing henge, so maybe they represent two different cultural groups that overlapped in time.

Wales also has plenty of the hilltop forts that characterize the Iron Age, when defense became critical, but we didn't happen to hike by them. The Iron Age is also when you first find individual burials of whole bodies, rather than of excarnated bones. Evidence suggests that folks then lived in large round houses, with thick wattle-and-daub walls and thatched roofs, as shown in this reconstruction.

We also had some fine hill walking, quite apart from ancient remains. The charming town of Beddgelert, a hiking center since the 19th century, was just up the road from Penrhyn.

There are some very nice valley and hilltop trails in that area.

This mountainous area underwent a significant mining boom in the late 18th to early 20th centuries, mostly for slate and copper. The high valleys were filled with now-ruined towns and mine buildings, and many of the current hiking trails were originally narrow-gauge railways for shipping out the slate.

If you look closely at this fairly steep trail, you can see the pairs of holes in each rock (best seen in the rocks on the right) that supported the tramway rails.

Slate is a metamorphic rock where the horizontal sedimentary layers were later compressed and sheered as if by rams pushing in from the sides. Thus the splitting plane of the slate is actually at right angles to the bedding plane as the rock was originally deposited. To mine it, they would break off large chunks, using black powder in a hole drilled using a weighted drilling pole that was turned a bit each time over many hours. Then the chunk would be transported to a surface workshop where it would be split with a wide chisel into narrow sheets and then trimmed to one of the standard sizes. Thus were the slate roofs fashioned for all of Victorian England.

One of the larger former slate mines now takes tourists down so that you can see what the mine caverns were like.

90% of the slate brought to the surface turned out to be flawed or didn't split cleanly. The huge heaps of waste slate are still very much in evidence in the high country.

With all that slate around, they used it for stuff besides roofs.

A number of the narrow-gauge railways are enjoying a second life as tourist trains, powered by their original 150-year-old steam engines, and largely staffed by groups of enthusiastic volunteers.

The narrow-gauge line that goes through Penrhyn includes the only railroad spiral in Wales. Spirals are used to ascend steep hills by rising on a steady curve until the line has completed a loop passing over itself as it gains height, so as to gain vertical elevation in a relatively short horizontal distance. Looking down from the train window, you can see the train is crossing over its track here.

The Penrhyn station also has the smallest roundhouse that we've ever seen, just large enough for a two-axle car.

While we're talking trains, we should perhaps mention the train station (on Anglesey) with perhaps the longest place name in the world. Only the first five syllables are the original name of the settlement, Llanfair (the parish "llan" of (St.) Mary "M/Fair")) in Pwllgwyngyll (the township called "the hollow of the white hazel"). The rest of the name, describing additional features of the area, was added in the 1860's as an inspired publicity stunt building on the general sense of long and unpronouncable (to the English) Welsh place names. Northwest Wales is the one area where the Celtic language is still in fairly common use.

From Penrhyn, it's not far to the Llŷn peninsula. The monastery on Bardsey Island, at the tip of the peninsula, was a major pilgrimage site in the Middle Ages. Along the north shore of the peninsula, we passed this well-preserved Tudor church (late 1500's), much larger than would be needed given the size of the small village that it's in, which supported and was supported by the many pilgrims on their way to Bardsey.

The organ, while not original, still dates from before electricity came to the village, as shown by the pump lever.

When stray dogs disturbed the service back then, they had ways of dealing with them.

On Llŷn, we also got to walk a bit of the coastal path, a hiking trail that follows the whole coastline. That's Bardsey Island across the water in the second picture.

On each end of our week in Penrhyn, we spent a day or two in south-eastern Wales. We had a spectacularly sunny day for hiking in the Brecon Beacons, a mountainous area where the peaks are mostly flat due to a layer of harder rock that resisted the smoothing effect of the glaciers.

There was still some snow up there, and we had lunch by a charming tarn, just below the peak.

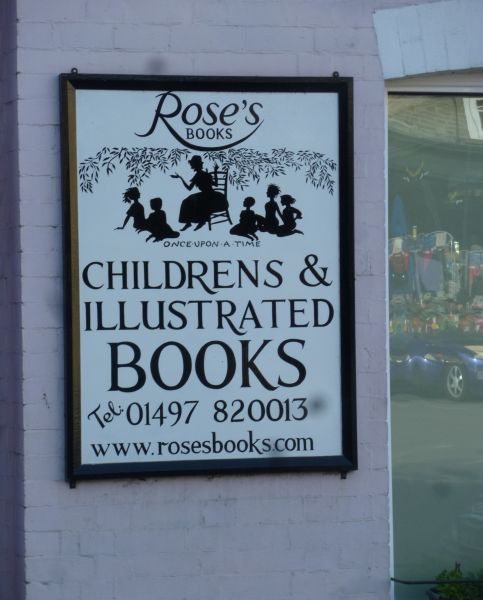

While in that area, we stayed near the village of Hay-on-Wye, which became a used bookstore mecca in the last century after an enterprising person opened one store there and talked it up.

It's not good times for used bookstores these days, but the town is broadening its tourist appeal with a large annual literary festival.

We'll end with the cutest surprise of the trip, which we discovered (all unknowing) when walking around the outside of Cardiff Castle.

Here's what we saw, peeking over the wall around the castle gardens.

The first set of figures, of which those were samples, were sculpted by Thomas Nicholls in 1890. Others were added by Alexander Carrick in 1931.

Back to ramshaw.info home page

Updated 2010-06-07